Eucharist

The other sacraments, and indeed all ecclesiastical ministries and works of the apostolate, are bound up with the Eucharist and are oriented toward it. (CCC 1324)

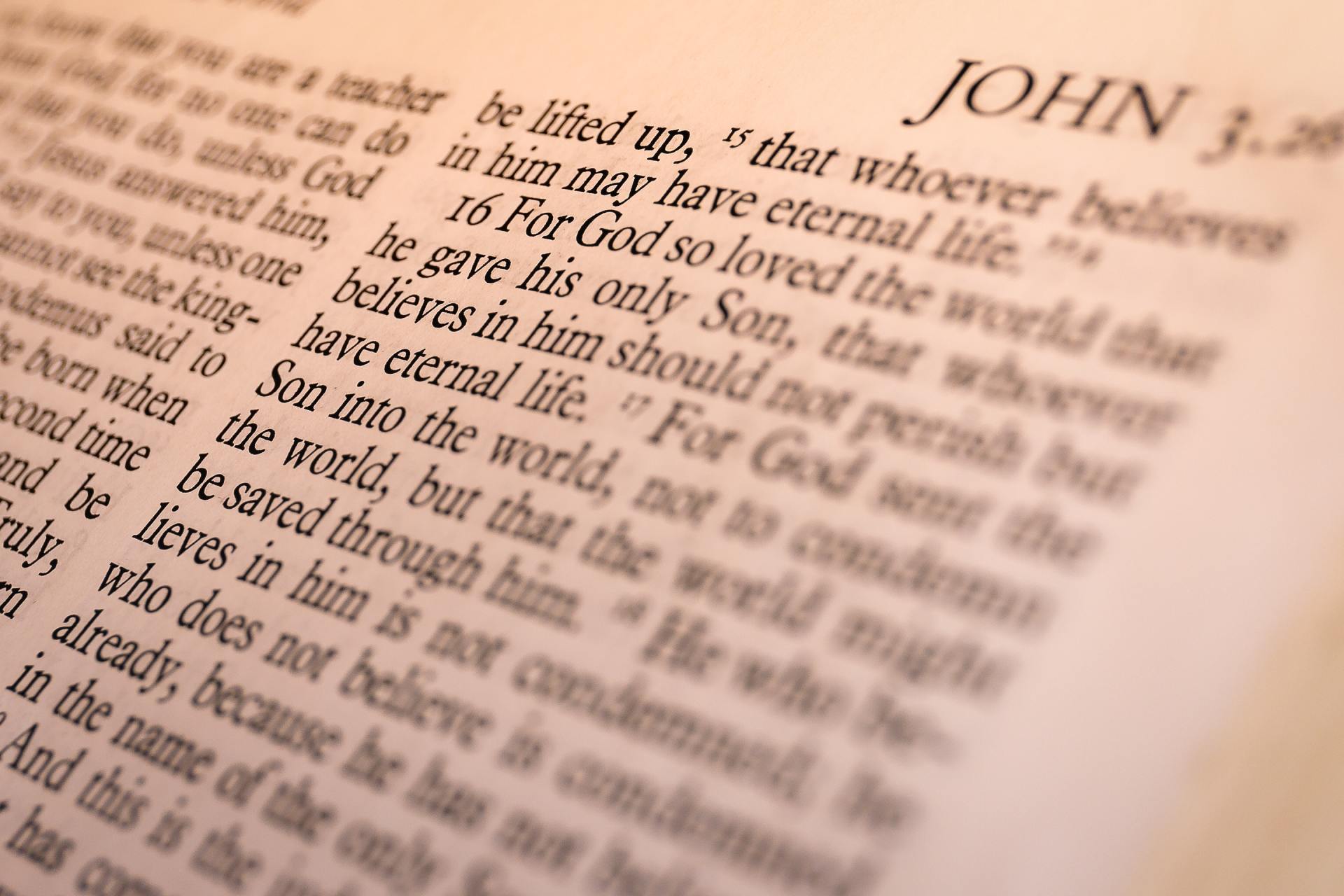

The New Covenant

Understanding the Mass

La vida litúrgica de la iglesia gira en torno a los sacramentos, con la Eucaristía en el centro (directorio nacional de catequesis, #35). En la Misa, somos alimentados por la palabra y nutridos por el cuerpo y la sangre de Cristo. Creemos que el Jesús resucitado está verdaderamente y substancialmente presente en la Eucaristía. La Eucaristía no es un signo o símbolo de Jesús; más bien recibimos a Jesús mismo en y a través de la especie eucarística. El sacerdote, a través del poder de su ordenación y de la acción del Espíritu Santo, transforma el pan y el vino en el cuerpo y la sangre de Jesús. Esta es la llamada transubstanciación.

Por el consecration el transubstanciación del pan y del vino en el cuerpo y la sangre de Cristo se trae alrededor. Bajo las especies consagradas del pan y del vino, Cristo mismo, vivo y glorioso, está presente de una manera verdadera, real y sustancial: su cuerpo y su sangre, con su alma y su divinidad. (CCC 1413)

El nuevo pacto

Yo soy el pan vivo que bajó del cielo; quien coma este pan vivirá para siempre; ... Quien come mi carne y bebe mi sangre tiene vida eterna y ... permanece en mí y yo en él. (Juan 6:51, 54, 56)

En los Evangelios leemos que la Eucaristía fue instituida en la última cena. Este es el cumplimiento de los pactos en las escrituras hebreas. En las últimas narraciones de la cena, Jesús tomó, rompió y dio pan y vino a sus discípulos. En la bendición de la Copa de vino, Jesús lo llama "la sangre del Pacto" (Mateo y Marcos) y el "nuevo pacto en mi sangre" (Lucas).

Esto nos recuerda el ritual de sangre con el cual el Convenio fue ratificado en el Sinaí (ex 24)--el rociado la sangre de los animales sacrificados unió a Dios e Israel en una relación, por lo que ahora la sangre derramada de Jesús en la Cruz es el vínculo de unión entre el nuevo socio del Pacto s--Dios el padre, Jesús y la iglesia cristiana. A través del sacrificio de Jesús, todos los bautizados están en relación con Dios.

El Catecismo enseña que todos los católicos que han recibido su primera Santa Comunión son Bienvenidos a recibir Eucaristía en la misa a menos que el pecado sea un estado de pecado mortal.

Cualquier persona que desee recibir a Cristo en la comunión eucarística debe estar en el estado de gracia. Cualquier persona consciente de haber pecado mortalmente no debe recibir la comunión sin haber recibido la absolución en el Sacramento de la penitencia. (CCC 1415)

La iglesia recomienda calurosamente que los fieles reciban la Santa Comunión cuando participen en la celebración de la Eucaristía; ella les obliga a hacerlo por lo menos una vez al año. (CCC 1417)

Recibir la Eucaristía nos cambia. Significa y afecta la unidad de la comunidad y sirve para fortalecer el cuerpo de Cristo.

La comprensión de la masa.

El acto central de adoración en la iglesia católica es la Misa. Es en la liturgia que la muerte salvadora y resurrección de Jesús de una vez por todas se hace presente de nuevo en toda su plenitud y promesa – y tenemos el privilegio de compartir en su cuerpo y sangre, cumpliendo su mandato mientras proclamamos su muerte y resurrección hasta que llegue AGA en. Es en la liturgia que nuestras oraciones comunales nos unen al cuerpo de Cristo. Es en la liturgia que más plenamente vivimos nuestra fe cristiana.

La celebración litúrgica se divide en dos partes: la liturgia de la palabra y la liturgia de la Eucaristía. Primero escuchamos la palabra de Dios proclamada en las escrituras y respondemos cantando la palabra de Dios en el Salmo. La siguiente palabra está abierta en la homilía. Respondemos profesando nuestra fe públicamente. Nuestras oraciones comunales se ofrecen para todos los vivos y los muertos en el credo. Junto con el que preside, ofrecemos a nuestra manera, los regalos de pan y vino y se les da una parte en el cuerpo y la sangre del Señor, roto y derramado por nosotros. Recibimos la Eucaristía, la verdadera y verdadera presencia de Cristo, y renovamos nuestro compromiso con Jesús. ¡ Finalmente, nos envían para proclamar las buenas nuevas!